“Her art is powerful and expresses femininity, sensuality, and also relates to a range of social considerations.” – Dr Geoff Raby AO, former Australian Ambassador to China (2007-2011)

What does a grenade look like from the inside?

Before I met Rose Wong, I could not have imagined that anyone would depict war in a language that is sweet, juicy, and almost seductive. A grenade, the symbol of violence, is divided in half, revealing a vibrant microscopic view beneath its skin. Whether it be an open heart or an exotic fruit, it is the look of a miniature world. I am drawn to the artist’s thoughts. Entering this world, I find the lives of individuals who have been left in darkness, reading subtle metaphors that have been long lost in silence.

Diseases, disasters, and wars – more than ever before, we are experiencing a mass of unanticipated events that remind us of society, nature, and destiny that we share. In the face of a rapid acceleration of emergence and evolution, and the formation and manipulation of our collective memory driven by data models and media opinions on a massive scale, where should an artist set the direction of their gaze?

“The personal, little, and even seemingly futile,” said Rose, a well-trained artist who untangled the mess with her intuition. She believes that all that is collective and macro is made of individuals and micros, and art is a miracle that resonates within our tiny souls. From “Han Fu” (汉赋) to “Song Lyrics” (宋词), through the story of a woman longing for her husband’s letter from the frontier, Rose drifts into the river of time and learns to understand war.

Like her art, delicate but resilient, innocent yet powerful, Rose is an individual of fascinating complexity and contradictory “other sides”. She is a cross-disciplinary artist who seeks balance working as an artist, curator, author, researcher and educational app producer for children. Her ancestral homeland marks the starting point of the Maritime Silk Road in Fujian; her life is marked by a completely different identity since she was born in the colonial era of Hong Kong – “Rose”, an English name chosen from the dictionary by her parents who could not even fully recite the 26 alphabetic letters. Trained at the University of Hong Kong and Goldsmiths, University of London, she put aside her Western educational background and dived into Beijing’s brutal winters. She lives an apparently distinct life from most “Bei Piao” (北漂) artists, moving from the outskirts to the heart of the city, and has finally settled in an ordinary neighbourhood, close to “man in particular” (note: as opposed to mankind as a whole1) and the shock and nourishment from the real world that she has been yearning for. Here, she has built a temple for her body, soul, and dreams. She wrote in the belated springtime in Beijing this year, “everyday ordinary life is indeed the April of this world.”

For Rose, the material is the language. She once found a special lace-like fabric in Berlin. At first glance, its delicacy is nothing different to that of ordinary lace, but when touched, it is sharp and nearly indestructible. She uses resin frequently in her art, a medium with a sophisticated sheen of amber, but is durable, waterproof, air-blocking, and time resistant. She was first aware of her preference for materials as an overseas student at Goldsmiths. In the late 1980s, the Young British Artists (YBAs) movement came to prominence in the art world. Some of the notable figures including Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas were trained at Goldsmiths. However, for Rose, the experience of studying here has been “confusing”. Compared to the trendy genres such as conceptualism and new media art, her medium is far from fashionable, and her passion for objects is perhaps too traditional for the interesting time we live in. “Wu Hung’s writing has inspired me greatly. According to him, from the origin of ‘the rites and music of the Duke of Zhou’, Chinese culture has always been about expressing emotions through objects and seeing objects as the carriers of emotions. I begin to realise that the way I express my emotions is deeply rooted in Chinese aesthetics, despite the Western academic training I have received over years.”

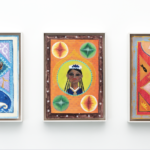

Her obsession with materials never stops in her art. The Bible of Female Saints is a new series Rose started in 2019. It contains a collection of female folk tales from different cultures, a few of which existed in history and the rest has been passed on without authoritative documentation and endorsement. As shown in this exhibition, the female protagonists are not presented in a realistic style. Rose intentionally borrowed first-hand material as her vocabulary and painted the women in materialised forms of stone statues, small gold figures, and reliefs. It reminds me of how they were deified as saints to convey moral teachings, materialised as cultural ornaments, and seemingly lightly embedded in our life.

In the creation of The Bible of Female Saints, Rose draws inspiration from her trip to Xinjiang. She travelled six times to Xinjiang in 2019, to live with the local people of minority ethnic groups, singing, dancing, and making crafts together. From the Kyrgyz Mother Deer to the Uygur Imperial concubine Xiang who had been confined to a political marriage with the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty, stories collected here have provided her with endless inspiration. “Xinjiang feels like destiny to me,” as she puts it. It is perhaps appropriate to call this journey a quest for the motherland. The vast land on the Silk Road frequently reminds her of Fujian, the post on the Maritime Silk Road, where she was carried in the arms of her grandparents as a little girl. She has established a sense of personal resonance from the cultural clash she experienced and found her answers to the unresolved nostalgia, the fascination with non-Western epistemology, and the obsession with minority subcultures.

A woman artist growing up in a subcultural context, Rose naturally finds feminism as her native language. However, as Rose tries to convey through her work, the challenge to social stereotypes and the reflection on discipline and indoctrination are a real and personal introspection of inner struggles. It should not be restricted to discussions of the external cultural environment, nor be used as a symbol of “herstory” to fight against “history” with the gender binary. It is a question that awakes us all: “Should I be a good girl, or challenge and annoy people?”

Notes:

1 “I love mankind,” he said, “but I find to my amazement that the more I love mankind as a whole, the less I love man in particular.” ― Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

– written by Man Luo, co-curator of Dorveille