An excerpt from Susan L. Beningson’s recent article, ‘Summoning Memories: Art Beyond Chinese Traditions’. Source: Arts of Asia Summer 2023 Magazine.

Language and Scholarly Traditions: Remembered and Reinvented

“One of the highlights of this exhibition is Xu Bing’s iconic hand scroll, the original painting of his Introduction to Square Word Calligraphy (New English Calligraphy), 1994-1996, that was later reproduced in the form of a printed book. Xu Bing’s two hanging scrolls, Square Word Calligraphy: The Song qf Wandering Aengus Poem by William Butler Yeats, and the rarely seen preliminary drawings for the two paintings are also on display in the exhibition. In Xu’s paintings, the Yeats poem is read from left to right, following English word order, and from top to bottom in columns, as in traditional Chinese texts. In 1993, when he was living in Brooklyn, New York, Xu began developing Square Word Calligraplry, an unique conceptual language organised in square blocks shaped like Chinese characters, but composed of English letters. The Introduction to Square Word Calligraplry is meant to be a textbook on how to write his new language: in describing the brushwork, the horizontal stroke should be strong and taut “like a bridled horse, not a rotted log”, and the brush movement for a left-falling stroke should be strong “like an elephant tusk, not a mouse tail”. Xu has said: “Through this kind of English calligraphy, I gave the West a calligraphic culture with an Eastern form. This text is suspended between two concepts. It belongs, and yet doesn’t belong, to both sides. v\Then people write it, they really don’t know whether they’re writing Chinese or English. If I had continued living in China, this work would definitely never have appeared, because the cultural conflict wouldn’t have been so direct. And it wouldn’t have become such a vital problem for me. It was a result of my living in New York.”6 Some of the visitors in the exhibition must have felt the same way, as one family tried to read the characters as if they were Chinese until they realised that they were English letters. Tao Aimin’s artistic practice explores the daily lives and often forgotten personal histories of women in rural China. Here she creates ink rubbings from wooden washboards collected on trips to her family’s home village, in similar fashion to those traditionally made from stone steles and calligraphic inscriptions in premodern China. She then inscribed the scrolls, on which the rubbings were mounted, with stories in the women’s language, known as nushu, a colloquial language spoken exclusively by the local women of the Yao minority in Jiangyong county, Hunan province, where nushu was invented and used. Tao writes: “So why did I combine the Jiangyong nushu with washboards? Because I think that the Jiangyong nushu is a language, just as the washboards are a type of language-they both tell stories… These rubbings were all printed using washboards.

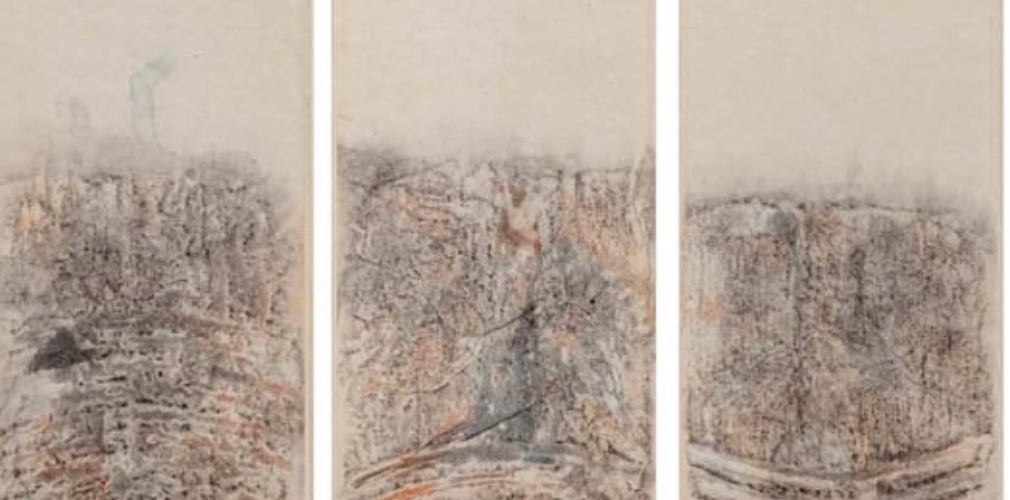

I did not use my hands. I just let the ink run down by itself… I have elevated the washboards to give them the status of traditional Chinese literati ink paintings. The lines on the washboard and the flowing ink… also look like rip ples in water.” She continues discussing the painting dis played at Asia Society: “In a Twinkle is very long, about three metres. I came up with the title because the patterns of the washboards reminded me of fingerprints… It creates the feeling of an ink landscape, but it was printed with the type of washboards that have bottle tops nailed on them. I used rice paper. It looks a bit like the Dunhuang frescoes because of its blurriness and the way it settles.” The niishu inscriptions at the top of each of the three hanging scrolls describe relationships between family members and very personal hardships faced by the women in her rural village.